Maritime security – EU naval mission sails in troubled waters

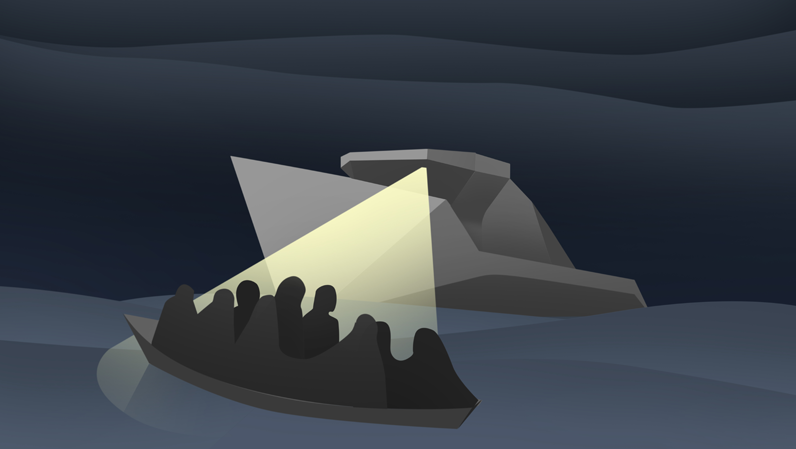

Tim Compston, Features Editor at Security News Desk, looks at European Union naval operations tackling people smuggling in the central Mediterranean – one year on – in the wake of a damming House of Lords Sub-Committee report.

This is certainly an opportune moment to take stock of what is actually happening in the seas between Libya and Italy with regards to the trafficking of migrants and the attempts being made to interdict such activity in what, given recent news reports, are undoubtedly difficult and tragic circumstances. Despite criticism from some quarters that it hasn’t done enough on the people smuggling front, especially with regards to tackling the traffickers in coastal waters, the mandate of the EU Naval Force Operation – EUNAVFOR MED (Operation Sophia) – has just been extended for another year. Of course, as we will see, having a volatile situation in Libya certainly hasn’t helped matters.

So how big is the people smuggling problem at the moment? According to figures provided by the UK MOD the number of refugees and migrants crossing the Mediterranean to Italy since the start of January this year amounts to over 25,000 with many of those originating in Sub-Saharan Africa, including 18 percent from Nigeria. Although this is still relatively small fry compared to the 180,000 who made their way to Greece, all the signs show that trafficking activity is likely to pick-up pace as we enter the summer period when conditions at sea are more favourable.

A naval view

Speaking in defence of the EU operation in the Central Mediterranean, Lieutenant Rino Gentile from the Italian Navy, who is based at the headquarters of EUNAVFOR MED – Operation Sophia, is quick to stress that all activities associated with this critical mission have to be conducted in accordance with international law and under the authority of UNSCR (United Nations Security Council Resolution) 2240.

Asked whether the priority of the operation to date has been to save lives or to stop the people smugglers themselves, Lieutenant Gentile responds that first and foremost it is about contributing to the disruption of the smugglers’ business model by denying them freedom of movement and, crucially, ‘neutralising their vessels and ‘enabling’ assets’. When it comes to saving lives, Lieutenant Gentile says that although Operation Sophia is not a search and rescue mission per se, all assets are still bound by law to respond to Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS) situations: “The rescue of persons at sea is also part of the DNA for any mariner. We have and will continue to respond to these events under the co-ordination of the relevant Maritime Rescue Coordination Centre (MRCC). Indeed, from the start of the mission until May 23rd we have rescued over 13,800 migrants.”

This was, Lieutenant Gentile explains, during 84 rescue events coordinated by the relevant Italian Maritime Rescue Coordination Centre. An additional 31,096 migrants he confirms have been rescued by other actors in the area with the contribution of EUNAVFOR MED assets.

Mission phases

Lieutenant Gentile adds that, in practical terms, the operation is actually designed to run in four distinct phases: “The first consists of the deployment of forces to build a comprehensive understanding of smuggling activity and methods [this phase is now complete].” Phase two, which is active, is where smugglers’ vessels can be searched and diverted on the high seas. This, he says, could eventually be expanded into relevant territorial waters if there is a suitable UNSCR plus the consent of the state concerned: “The third phase, subject to the necessary legal framework, would see EU naval forces taking measures against vessels – and the associated assets – related to smuggling inside the coastal state’s territory itself.” According to Lieutenant Gentile, the last, and fourth, phase is basically when things are brought to a conclusion with the withdrawal of forces and competition of the operation.

Measuring success

With regards to the impact which Operation Sophia has had on the modus operandi of the people smugglers, Lieutenant Gentile contrasts what was common practice around phase one of the operation with phase two: “During the mission’s first phase we witnessed that migrants’ boats were escorted by the traffickers until well inside international waters. Now [with phase two] it is not like that anymore, the smugglers and traffickers remain far away as they fear being apprehended.” Lieutenant Gentile believes that, especially in the second phase where naval units are authorised to board, search, seize and, if necessary, divert suspicious vessels on the high seas, Operation Sophia represents an effective deterrent: “Smugglers and traffickers have limited their operations to Libyan territorial waters and are not coming anymore onto the high seas to recover migrant boats as happened in the past,” he concludes.

Drilling down to some more specific metrics regarding the positive impact of Operation Sophia as of May 23rd 2016, the course taken by EUNAVFOR MED has resulted in 69 suspected smugglers and traffickers being prosecuted by the Italian authorities. Beyond this, Gentile says that the mission has prevented 119 boats – 91 rubber, 24 wooden, and three fishing vessels – from being re-used by the smugglers.

In terms of whether there has been a surge in activity in the central Mediterranean as people move away from other routes, Gentile says that, at the moment, this does not appear to be the case but with the closure of the Balkan route and the arrival of the summer he expects that numbers will rise again: “We have lots of different figures but I can say that at least 150,000 will arrive: “They [migrants] may choose the most dangerous route going South to Sudan and then coming North – because Egypt will not allow them to cross the country – or they can take the sea from Syria and Lebanon directly to Italy or Greece as was the case in 2013 when they used big mother ships or merchant vessels.”

Additional tasking

So where do things go from here? Well with Operation Sophia’s mandate being extended for another year, Lieutenant Gentile tells me that the European Council has added two further supporting tasks, specifically: “Capacity building and training of, and information sharing with, the Libyan Coastguard and Navy, based on a request by the legitimate Libyan authorities.” The other supporting task, which Lieutenant Gentile flags up, is to contribute to information sharing as well as the implementation of the UN arms embargo on the high seas off the coast of Libya on the basis of a new UNSCR (United Nations Security Council Resolution).

In closing, Lieutenant Gentile is keen to underline the international nature of the mission thus far: “At the moment 24 EU member states are participating with 1,500 people part of the international staff working in the Operations Headquarters in Rome, the staff embarked on-board the flagship [the aircraft carrier Cavour] in support of the Force Commander, all the naval and air assets’ crews – they represent the real heart and mind of the operation.”

House of Lords report

Of course the EU NAVFOR MED mission is certainly not without its critics and a recent report by the House of Lords has created significant waves in this regard. Speaking during the launch of the report back in May, Lord Tugendhat, Chairman of the House of Lords EU External Affairs Sub-Committee, explained why such an inquiry was necessary in the first place: “Everything to do with immigration is extremely topical, there is a lot of publicity attached to what is happening in the Mediterranean. Operation Sophia itself has been going for a year. It was coming up to the decision as to whether it is going to be renewed or not and this seemed to be a good moment in which to review what has happened [and to make an input into the decision that has to be taken].”

Lord Tugendhat did acknowledge that the mission is saving many lives: “That is a very important consideration but what it [Operation Sophia] is not doing is stopping or interrupting the flow of migrants across the Mediterranean and nor has it been able to get to grips with the business model of the people who are actually organising the trafficking.”

For Lord Tugendhat the biggest dilemma which Operation Sophia continues to face is the lack of any sort of stable government in Libya: “That [Libya] is a point of departure for the migrants. Where you have a stable government, as for instance in Morocco, there is very little movement of people across the Mediterranean but in Libya there is no stable government and therefore it is an open area for the people organising the smuggling.”

Looking at the limitations of Operation Sophia, Lord Tugendhat said that there are really two principal issues muddying the waters: “One is that it [the mission] is unable to arrest the key organisers of the smuggling because they don’t go on the rubber dinghies and wooden boats and so forth. It is unable also to undertake serious intelligence gathering. It can’t of course go ashore in Libya, it can’t indeed go inshore, and therefore it is operating, if not with one arm behind its back, with one and a half arms behind its back.”

Despite the disappointments as he sees them, Lord Tugendhat pointed out that the House of Lords report still, in fact, recommends that the mandate of operation Sophia should be renewed in the hope that a stable government may emerge in Libya, one with which the member states in the European Union could work: “That remains to be seen but we should be ready for it. We also must remember – and we point this out – that the movement of people across the Mediterranean is part of the mass migration of people from poorer countries to richer countries and that is going to require a much more thought out coordinated policy response. It is something which is of deep concern to people all over the European Union and we point the way towards trying to persuade people to take that seriously,” he concluded.

British contribution

In terms of the UK’s input into Operation Sophia and the wider effort in the Mediterranean an MOD (Ministry Of Defence) spokesperson confirmed to SecurityNewsDesk that, since May 2015, Royal Navy assets and Border Force Vessels have rescued almost 18,000 people as well as intercepting suspected people smugglers. The UK, he reports, is also involved in Frontex search and rescue missions in the area with the Home Office having chartered a civilian vessel – VOS Grace – for this purpose which is deployed with detachments of Border Force officers and Royal Marines.

Returning to Operation Sophia itself the MOD spokesperson says that the UK currently contributes HMS Enterprise – a multi-role survey vessel – for this purpose. Although, as the MOD spokesperson acknowledges, Operation Sophia is not a search and rescue mission, with the primary purpose of the mission being to seize smugglers’ vessels, he says that naval assets like HMS Enterprise will still continue to respond to boats in distress.

At a diplomatic level the MOD spokesperson flags up the fact that the UK has been very supportive of the mission and, he point outs, was actually instrumental in securing the United Nations Security Council Resolution (UNSCR) supporting the second phase of the EU Naval Force Operation in the Mediterranean.

Change in Libya

Considering the current situation in Libya, with its 1,700 kilometres of coastline, which is impacting so directly on people smuggling activity across the Central Mediterranean route, the MOD spokesperson sees a glimmer of hope amidst all the recent turmoil: “At this stage what is needed is a Government in Libya with whom we can work so we can cooperate with the Libyan Coastguard, in Libyan waters, to turn back the boats and the smugglers there too. There is now a new Prime Minister and a Government that we have recognised as the sole legitimate authority in Libya. These are still early days but we must do what we can to make this work.”

The big picture

Ultimately, the situation which the EU Naval Force finds itself in is far from ideal with many of the factors impacting on the success, or otherwise, of the EU’s anti-people smuggling mission firmly outside its control. The hope has to be that should some semblance of order return to Libya then there will be more scope for EU naval assets – including those from the UK – to clamp down on the people trafficking operations at source, allowing the naval mission to finally extend its focus to the coastal as well as the international waters off Libya.

[su_button url=”https://www.securitynewsdesk.com/newspaper/” target=”blank” style=”flat” background=”#df2027″ color=”#ffffff” size=”10″ radius=”0″ icon=”icon: arrow-circle-right”]For more stories like this click here for the Security News Desk Newspaper [/su_button]

*Header Image Credit: EUNAVFOR MED