The interview lasted just a minute and didn’t go at all the way I expected it to. The presenter came on with a very argumentative point about there being too many CCTV cameras and these represented a real threat to our civil liberties.

I countered that CCTV was a useful tool for protecting a very important civil liberty which is protection from crime and the interview was over almost as soon as it began.

You can listen to the interview below:

But there’s so much more that I wish I could have said.

The CCTV code of practice has been introduced as part of the Protection of Freedoms Act 2012 and outlines 12 principles for the use of CCTV surveillance cameras in England and Wales including:

- Surveillance cameras shouldn’t be installed unless there is a clearly defined purpose which is legitimate and can’t be achieved in another way

- They shouldn’t look into areas which you would reasonably expect to be private

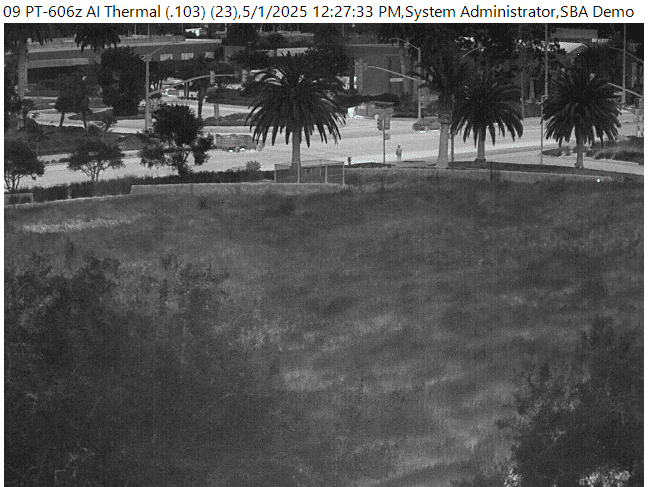

- The images should be accessible and usable – in other words, the system should be fit for purpose

- Plus it calls on cameras to be used with proportionality, transparency, and accountability.

Perhaps most importantly, it introduces the idea of surveillance by consent, an idea that the surveillance camera commissioner Andrew Rennison has borrowed from policing by consent. This is the idea that surveillance should not be imposed upon a community without consultation and consent.

Although there are few examples of CCTV being imposed without consent – most communities love it and want more – it is a wise response to the Project Champion debacle.

So that’s the code (in a nutshell), but what has it done for us? The answer is very little.

Introduced as a sop to the Liberal Democrats and the libertarian wing of the Conservative Party, the CCTV code of practice says little that hasn’t been said before by the Information Commissioner and the terms of reference of just about every public CCTV system in England and Wales.

While one could argue that it is a tentative first step toward more comprehensive regulation (and there are hints of this in the code and accompanying Home Office statements), it is quite disappointing when measured against the National CCTV Strategy which has languished on the shelf since it was published in 2007.

The Strategy document outlined 44 recommendations to help the UK get the most out of the hundreds of millions of pounds that has been invested in CCTV over the past few decades. There was great excitement in the CCTV industry when it was published because it was felt that the authors – among them Graeme Gerrard and Garry Parkins – had really “got it”.

For the first time, the Strategy document recognised that despite years of investment and the growing realisation of the value of CCTV in criminal investigations, there had been no strategic direction given by the Home Office in the development of these increasingly complex systems.

One would have hoped that with the creation of the CCTV commissioner, that strategic direction would have been forthcoming. Instead we have been given 12 principles which users of CCTV systems should “have regard to”. Enforcement is non-existent – the CCTV commissioner can only advise and monitor.

Worryingly, the code has the potential to hobble the development of new CCTV technologies if system owners are persuaded that the deployment of automated systems such as facial and behavioural recognition software would be criticised under the terms of the code.

I am particularly worried about the use of audio analytics. When paired with a CCTV camera, directional audio analytics enables a CCTV camera to listen out for audible signs of danger such as someone screaming for help or the sound of breaking glass. However, the code makes specific reference to audio recording which could be interpreted as a ban on these systems.

In addition, throughout the code there is the use of the word “proportionate” which I struggle to understand, because the interpretation of proportionate is very subjective. For instance, US president Barack Obama argues that intercepting emails and phone calls is a proportionate response to the threat of terrorism, and yet there are many of his own citizens who would disagree with him.

In my radio interview, I challenged the presenter Oliver Hides to give me an example of harms caused by CCTV, to which he responded that there was a general threat to civil liberties which had to be addressed.

I countered with the observation that protection from crime was a basic civil right. I wish I’d had more time to develop that thought, but I wanted to say that there are many specific examples where CCTV has been used to protect the individual, investigate crimes and bring criminals to justice.

The real harms that I see with our existing CCTV regime is that the industry is like the wild west: we have millions of poor quality systems being installed by private operators of CCTV in shops, clubs and quasi-public spaces which are of variable quality and in many cases extremely difficult for the police to use.

Because there is no need to register a system with a central authority, we have very little idea where to find the CCTV cameras in the event of a major incident, so thousands of hours of police time are wasted trawling for useful CCTV footage.

The police have been slow to adopt CCTV as a forensic science. The recent creation of visual identification units in some police forces is a major step forward, but there is still much to be done and its disappointing that the government has ducked this issue.

There are no mandatory standards for the use of CCTV as evidence in court, and in many cases courts are ill equipped to view CCTV even though it forms the crux of an increasing number of cases.

And finally, in its current incarnation, the office of the surveillance camera commissioner is a largely pointless one. Having produced the code of practice, what’s left for the commissioner to do apart from lecture the industry to adopt his recommendations?

One has to question the government’s commitment to maintaining even this level of so-called regulation when they have yet to advertise for a new surveillance camera commissioner to replace Andrew Rennison when he leaves in February 2014.

We were promised that an advertisement for his job would be published in the spring but here we are in mid-August, still waiting. What are the chances we’ll see an advertisement this side of October?

The publication of the CCTV code of practice is disappointing as it does very little to address the real challenges of CCTV which is a complete absence of a joined up strategy for making the most of the investment that has been made in this incredible technology.

- SecurityNewsDesk is proud to support the Global MSC Security Seminar in Bristol on November 12 which will look at “Making the most of CCTV”. For more information, please visit the Global MSC Security Seminar website.